the survival instinct

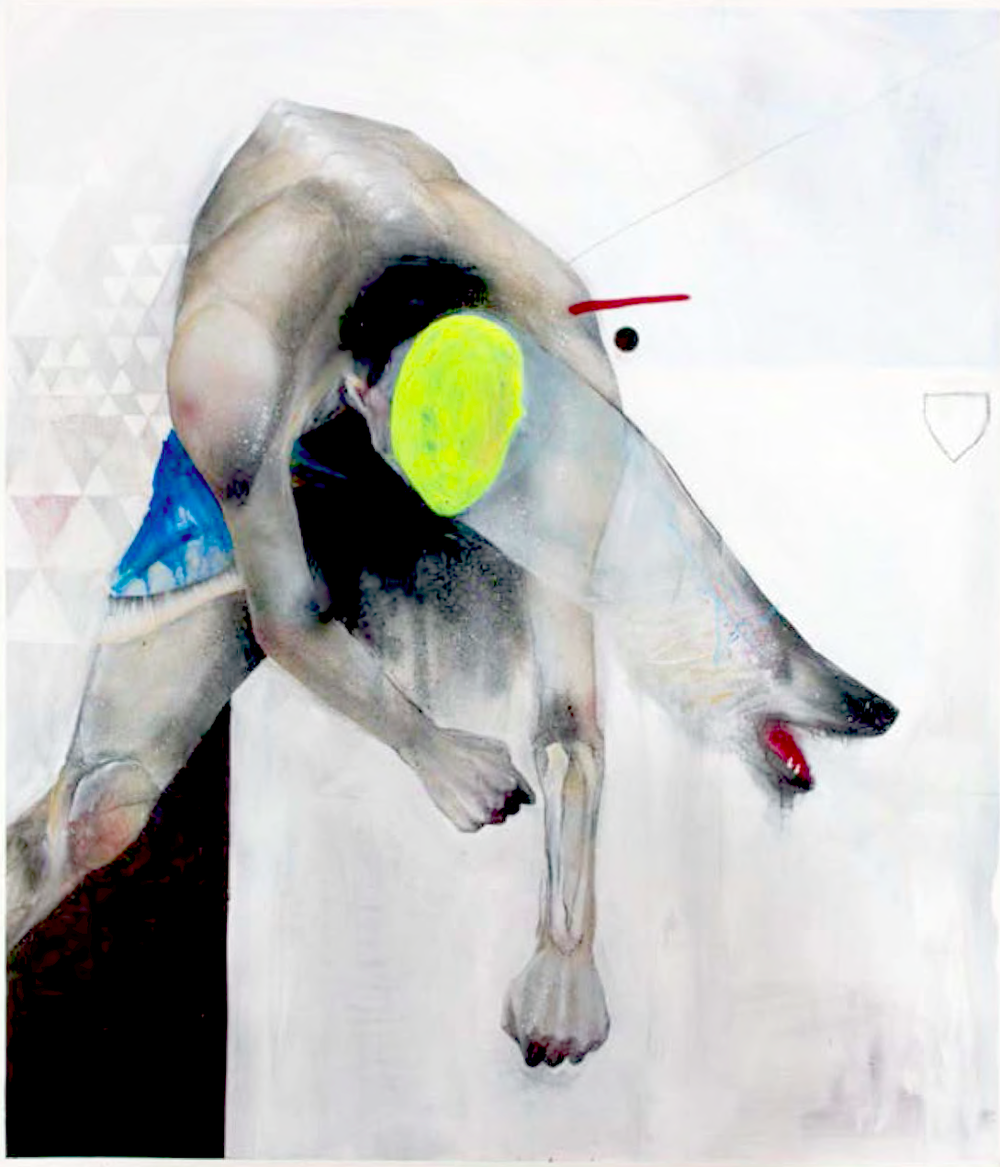

all artworks by Two One | Hiroyasu Tsuri

I often ponder the blissfully ignorant life of our house rabbit, Sadie, with not a care or concern in the world apart from: “where’s my food?” or “where are you, humans?”

Life is sweet, lounging on the couch with delicious parsley on the dinner menu; easily forgotten that rabbits in the wild are resilient and thriving survivors. In this luxurious existence, it’s not until poor health becomes a concern that the prey animal’s evolutionary instincts become apparent – that rabbits in the wild must conceal their ailments, because it’s the weak that a predator will target. Rabbit companions are instructed to seek medical attention immediately should a rabbit show signs of poor health, because an outward display of symptoms indicates that the ailment has reached a critical point. The rabbit so toughly persists through the pain until it may be too late.

Is the human animal so different?

The dichotomy of vulnerability and stoicism in dealing with pain or threat; there is a biological basis for this phenomenon in all animals, including us. It stems from the primal instinct for survival, with each species uniquely programmed with a genetically dictated, instinctive reaction to stimuli – such as the “fight or flight” response to a threat. Beyond these instincts, more intelligent animals have also developed traits and, due to a certain level of consciousness, learned certain behaviours that have been conditioned by their unique survival needs, environs and social structures. There’s the mentality of ambition; the innate desire to succeed, or even to be the best. Then, in the most intelligent animals, there’s the conscious ability to alter those genetically dictated instincts – they’ve adapted their behaviours to optimise the outcome of the circumstance. Animals exist within their species’ social structure, which I imagine to be like a ladder, each rung representative of varying degrees of survival success. With the juiciest fruits of the best life at the top of the ladder, we are all instinctively driven to climb there. Obstacles, such as pain and threat from predators, impede our progress along the way. Yet we clamber on. How often have you put on that brave face and gone to work, despite a raging head cold perhaps, because you wanted to prove yourself strong and worthy to a superior; or singularly persisted through a presentation despite debilitating, heartbreaking news about a loved one? Don’t show your weakness, lest you become the targeted prey.

I glance around the studio during class at the other dancers; lithe bodies of ready and robust musculature elongating and articulating with apparent ease. There is intent focus, but not a skerrick of exertion detectable on their finely formed faces. There is something akin to anticipation permanently hanging in the air – a sort of restless energy, a conglomerate of twitching minds and eager souls, always on alert, though calmly composed in their environment. I perform the same exercise that my colleagues have just completed, and only now do I comprehend the hard work that belies the outward composure. Calm faces take on an edge of noble bravery; they belie a rampant internal monologue of minute cognitive cues, the exertion of muscles being pushed to their utmost limit, and the silent protest of aches from the show the night before. I wipe my sweat-sodden brow and observe others doing the same. Some knead their knotted limbs on torturous rollers, with alternate sighs of relief and grimaces of agony. Others lean on the barre with their heads buried in their crossed arms, stretching out their spines as their ribcages heave with gasps for air. And yet when the next exercise is set, we continue.

A herd of deer, having just fled from a pack of wolves, has searched out a bounteous green pasture. There is a quivering buzz of freshly-frantic heartbeats, gradually decelerating to a normal pulse as they cautiously begin to graze upon the grass. Delicately sculpted faces are counterpointed by deepest dark but keen eyes – from afar the eyes appear sweetly at ease, but up close they nervously dart about. Graceful necks arch alternately between the ground, for food, and high in the air, to keep watch. Some are wounded, but that is only subtly apparent in the oddness of a gait, or the discreet nursing of an abrasion. They can’t rest indefinitely, but if they don’t feast now, they won’t have the energy to flee the next predator. They would not survive. There is something akin to anticipation permanently hanging in the air…

For us, it’s obviously not a life-or-death matter, no matter how melodramatic you are. Our survival mechanisms are evident in many aspects of our approach and response in our daily life, even though there is no real predator - at least in a literal sense. There are, however, threats to our progress, if we allow it, that may transpire in our responses to stimuli: the external - our superiors’ expectations, or the audience’s expectations; and the internal – our expectations of ourselves. The ballet world is an environment in which the pursuit for perfection heightens those expectations, in which the disciplined and relentless nature of the profession magnifies those demands, in which, at our worst, we find ourselves pushing through pain in order to prove our worth. To stay alive, in hope to thrive, we must learn to sense the first signs of the predator’s surreptitious stalk and demonic gaze, and flee from it. And if the predator already has you cornered, you must fight, sometimes with every last vestige of that artillery called Self-Belief that you have.

It’s well known that a professional dancer’s pain threshold is considerably higher than the average person’s (my awareness of this is renewed whenever I straight-faced tell people how pointe shoes feel like house slippers to me), but not so well-documented is the unrelenting challenge in accepting human weakness in the quest for perfection ideals and desire for the top positions, and how that relates to pain perception. Could brave faces just be foolish faces? No, but there comes a point of exhaustion at which sheer guts and grit has to yield to intelligent strategies for successful survival. A smart professional dancer has learnt, with the help of medical professionals, how to distinguish between different types of pain and navigate the grey areas in between. These professionals will also guide the dancer back to full strength in a tailored recovery program, designed to correct the off-kilter biomechanics that may have caused the injury, in a safe and nurturing manner. Dancers often remark that their heightened physical awareness as a result of this rehabilitation enriches their dancing. There is the obvious character-building aspect, too. Here is an example of how, as highly intelligent animals capable of altering our natural responses to stimuli, we can make the pain experience one of courage and growth rather than a perception of succumbing to weakness. This isn’t just the terrain of a professional dancer, nor is this evolutionary intelligence applicable only to physical pain.

The pressure of attaining and maintaining our position at the top of that ladder is an anomaly in that it constantly drives us to better ourselves, to reach for that fruit, but can also potentially destroy us. In a prestigious ballet company we are expected to be amongst the best dancers in the world, and this is extraordinarily difficult to live up to on a daily basis, and in every performance.

We are always on edge – anticipation hanging permanently in the air - the day after a season opens, we are in the studio the next morning rehearsing the upcoming season that likely opens only a few days after the current one has closed. There is little time for kudos. And we are rarely satisfied.

Ever onwards, sometimes persisting through ailments, often persisting through self-doubt, impelled by the primal urge to succeed, not just survive. The evolutionary instinct to conceal pain isn't exclusive to prey animals like rabbits. One of our closest relatives, chimpanzees, shares more than just DNA with humans.

The alpha male chimpanzee will hide any signs of illness or injury, because if he doesn’t, he may be ousted from his position at the top by a feisty young male, who sees the illness as an opportune time to challenge the alpha to a fight for superiority. Then all the perks of being at the top: a harem of mates, royal treatment, the best food, are all granted to him. The most ambitious of animals achieve dominance through physical fitness, special skills, intelligence and aggression. They maintain it by wearing a mask. Powerful and composed, belying an ever-ringing cacophony of fears and weaknesses.

Keep calm and carry on.

The madness-inducing monotony of constantly keeping face and maintaining the status quo. If we are so vastly superior to other species, what has so stunted our evolution and progress as to suppress the essence of being a happy and productive human: to liberate oneself from the shackles of expectation, to be comfortable in our own skin, to have the freedom to honestly express - even pain - without inhibition (with compassion or at least consideration for others of course), to feel with passion, to live without fear? To let our hearts guide us, with vigour and love for what we do, for others and for ourselves – that is courage, and, used with intelligent and decisive strategies, leads to progress. Accepting the easy solution even though it's a compromise, being guarded, deceitful or duplicitous, acting with agenda, lacking perception – this is weakness and indecision that only leads to friction and disillusionment for others. We become static, and no one dares to disturb.

Are we so blinded by ambition that this conformist, pack mentality is seen as the only viable path to success?

Conditioned by societal pressures, the yearning for the top can surreptitiously morph into singularity and greed all too easily. That greedy ambition has escalated in our results-driven, consumerist age: success equals power, and power can be addictive. There is nothing inherently wrong with pure ambition, but pursued with an imbalance of response to the external, rather than the internal, could surely only lead to superficial and transient happiness, and given its often unrealistic pressures, is potentially damaging for our souls.

So perhaps wearing a mask is a necessity, to keep everything in life "nice". No one wants to see someone who is placed upon a pedestal show weakness. They are placed there because everyone looks to them for inspiration, as a beacon of their ideals. And yet ruthlessness, or even cruelty, is also an innate animal behaviour. We can willingly tear these people apart -

this one's too strong, this one too soft, this one was just right until their vulnerability superseded their heroism.

Tall poppy syndrome, celebrity bashing, bullying, backstabbing gossip, sexism, calculating manipulation ... anyone and everyone can be fair game. There is no way to avoid it - everyone is fighting to survive and succeed in their own way, some more evolved in their behaviour than others.

The most successful of us humans, and of all animals, are the ones who have best adapted their intrinsic and learned behaviours to their advantage. Unfortunately, whether their intentions are noble and decent, or conniving and corrupted, is inconsequential in the grand scheme of that metaphorical ladder. This is the nature of the pursuit of power and survival in the modern world, one that is driven by the incessantly beating heart of our primal urges. It’s a dog-eat-dog world out there, and it’s up to us to decide whether we want to emerge from the battlefield with a clear conscience. Life’s trials, and threats, shape our progress and identity, and if humans have the ability to exploit that, why wouldn’t we evolve to coexist more harmoniously with and at the aid of others, and indeed the other animals with whom we share such common traits? Let’s not forget that feeling love and compassion are also instinctive behaviours. We can still achieve the prestigious top rung with grace and humility, along with stoicism and the occasional healthy acknowledgement of our human and animal flaws. We could be unstoppable in pursuit and in flight. The hunted might not become the hunter, but they’d cease to be merely easy prey. A resilient, thriving and successful survivor.

Thank you to Hiro ‘ Two One ‘ Tsuri for allowing me to use his beautiful art work to illustrate my writing. His art really speaks to me, and I'm sure you can understand why after reading this.