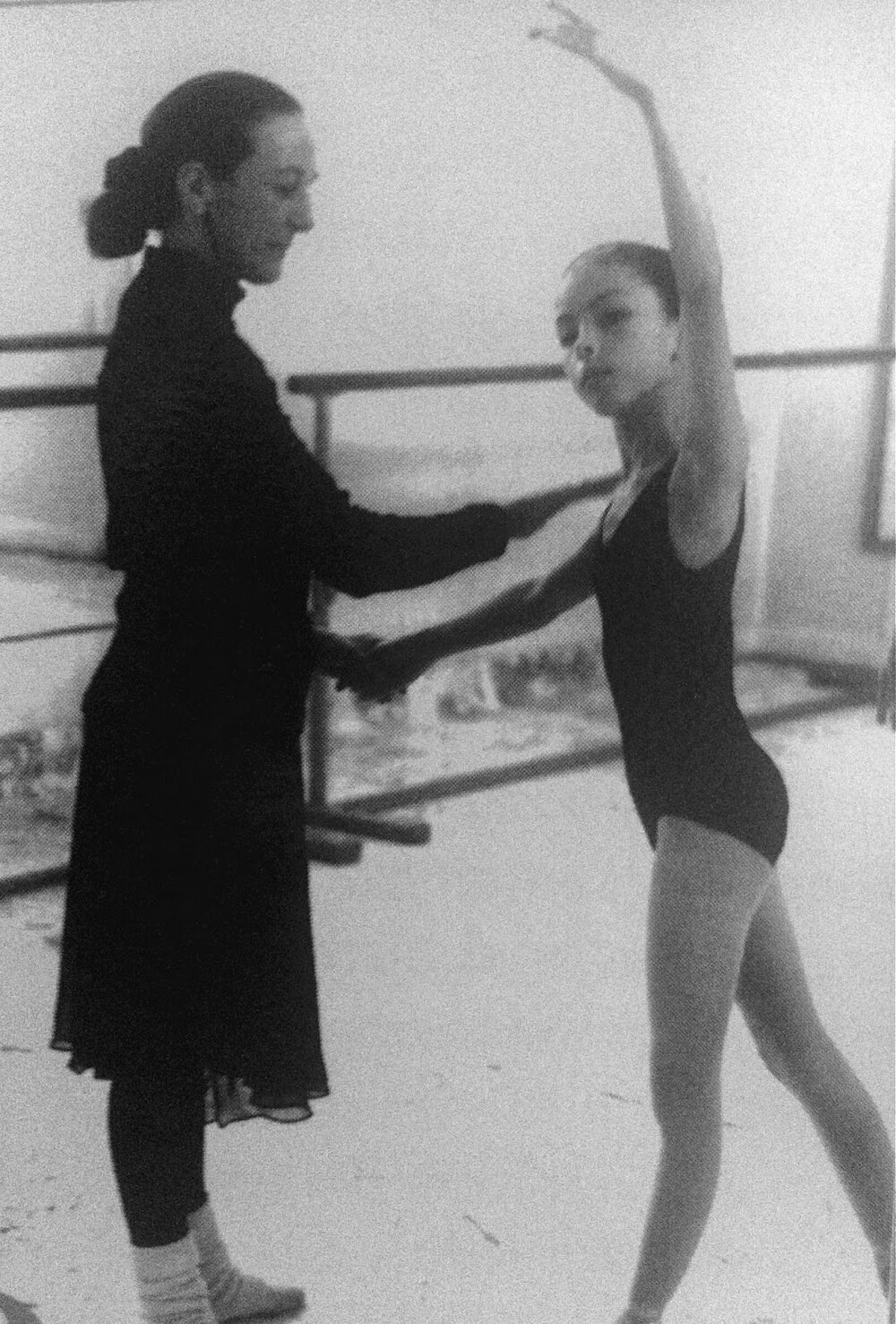

at the barre

me, aged around 10, with my teacher Valerie Jenkins

In this series I want to take you into my mind as I work through the dancer’s daily ritual of morning ballet class. Much like a swimmer’s morning laps, it’s a training essential for professional dancers in all ballet companies and also many contemporary dance companies. When we are in rehearsal periods, it’s for fine-tuning technique, developing artistry, increasing stamina, exercising mental intelligence, and warming up for the day’s rehearsals. When we are performing, while we are still working on those aspects, class becomes a more varied undertaking: a way of checking the body back in after the show the night before, for ironing and evening out a body addled by perhaps one-sided choreography, warming up for the day’s rehearsals; all with measured exertion so that there’s enough energy left for the show that night. Even though we have a different teacher and pianist each day, and the exercises that are set (on the spot) vary, it’s one of the only constant factors in a profession full of inconstants. It’s a daily chance to discover your body and its expressive possibilities. It can be confronting. It can be a meditation. It can be the highlight of your day, a confidence booster, or it can be frustrating and send you off on a low note. But it’s still our oxygen.

Today, the best word to describe my body was ‘discombobulated’. My right hip feels like it’s up by my ear, my ankles feel like they need a good spritz of WD40, and the entire left side of my torso appears to have been left behind in the USA, from where we have just returned after an outrageously successful tour of Graeme Murphy’s Swan Lake.

I’ve long resigned myself to the reality that a constant sensation of complete symmetry is elusive, but the pursuit of it and the expression of it is fundamental in classical ballet. To me, trying to achieve that equilibrium in the body is more about trying to find a neutrality, a connection from the core so that all movement and dynamics can emanate from the centre rather than the extremities. While it’s important to find a sort of ‘squareness’ and alignment of the torso and hips, this is for the purpose of being able to use it as a home base, a departure point for full movement, not to dance with a rigid frame in a rigid manner. One of our guest teachers, Johnny Eliasen, often uses the visual cue of Da Vinci’s great depiction of the symmetry and proportion of the human body, the Vitruvian Man. Classical ballet should be about purity of form and expression, and too often today, caught up in this obsession with quantity over quality, this purity is forgotten. Many of classical ballet’s pathways move in circles, so the encircled Vitruvian Man provides a perfect reference when executing a simple port de bras, the tips of the fingers reaching and drawing the shape of the circle around the body; or a rond de jambe, which, if you were to execute one at the beach, would leave the trace of a perfect semi-circle in the sand.

Leonardo da Vinci's Vitruvian Man

My appreciation for the purity of classical ballet can be accredited to my training in the Cecchetti method. Enrico Cecchetti was famously Anna Pavlova’s personal teacher, and ballet master of Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. His syllabus (I completed all the exams from Grade One to Advanced) was designed to develop expression and sensitivity but with a hallmark simplicity of style. There is no affectation of port de bras that so taints some other training methods. It’s honest dancing. Valrene Tweedie, who taught my teacher Valerie Jenkins and who also took me for special coaching, instilled in me a mantra that is still of foremost pertinence for me: “simplicity and sincerity”. I apply it to all my work, from class to rehearsal to performance. I think it has also become a bit of a life mantra.

Maestro Cecchetti and Anna Pavlova

So when, like today, my body feels like a slackly strung marionette, I go back to basics. More Pilates in my warm-up to reawaken the core and strengthen and lengthen the muscles. If the choreography favours one leg (Graeme’s choreography tends to favour the right leg), then I try to even out the load on the body by repeating the exercise twice on the unfavoured side. I start at the barre with more subtle movements and carefully measured exertion, to find the connection in the joints and gently ease the points of tension. In all the exercises, the focus is on placing the energies back into the centre of the torso, as though my body were a hive and I was summoning the bees, buzzing nearby but somewhat haphazardly, back home. After the long flight from LA, my neck was unbelievably stiff and my left shoulder seemed to only want to roll forward instead of rotating backward and gliding downwards, as is the ideal classical ballet posture. Even after a series of scapula placement exercises before class and a wariness of that placement and release of neck tension throughout class, any rotation of my head was restricted – kind of made spotting for pirouettes a frustrating ordeal. And so it was off to the physio room to book myself in for what seems to be transpiring to be a routine post-flight neck and upper back release.

It will take a few more days before the body reacquaints itself with its connections. This may be aided by the repertoire we are rehearsing: La Bayadére, with its stylised but still very classical ballet technique. When we perform classical ballets, whilst exhausting, they do help the body to feel 'more ballet' - pulled up and with an established equilibrium - in class. It is then that class will be about ensuring that my movement doesn't get too stiff, too precious or worst of all, contrived. But we have to travel to Sydney – yes, barely a week after our return from the US – first.